Share

Learning Outcomes

This piece investigates the ethical dilemma financial advisers may face in recommending digital assets to their clients. The purpose of the piece is to enlighten the reader with information on how the dilemma has surfaced, why it is necessary to resolve it, as well as provide potential solutions to diminish the impact of it over the short-term. Key issues that will be addressed include:

- The prevailing consumer and adviser sentiment regarding digital assets.

- The underlying psychological causes of biases one may have regarding digital assets.

- What impacts these biases may have, and solutions to manage these biases.

Introduction

Monochrome Asset Management provides the financial advice community with research to assist advisers in improving their communication about digital assets with their clients.

Having recently launched its services to the financial advice community, Monochrome has received encouraging feedback, but nonetheless recognises the challenges that many advisers face when discussing this asset class with their clients. A key question arising from the financial advice community is, ‘how does one manage implicit biases; both one’s own biases and biases of clients?’

There is no shortage of controversy surrounding the digital asset ecosystem. Controversy, by its very nature, causes a polarisation of opinions. Typically, the greater the degree of polarisation, the greater the risk of clinging too firmly to prejudices which can impede the adoption of new ideas and opportunities.

This paper aims to address some of the underlying causes of biases when considering digital assets. In particular, it focuses on cognitive dissonance and the risks this bias poses to both advisers and clients. It then discusses solutions to managing this bias.

Today, it is not easy to provide advice on digital assets. This nascent asset class is not clearly defined by the Australian Securities and Investments Commission (ASIC) for advice purposes. This inhibits responsible entities and licensees from recommending digital assets, and professional indemnity insurers from offering cover. That said, it does not mean that an intelligent conversation cannot take place with clients.

Consumer Sentiment & Adviser Hesitancy

Digital assets like Bitcoin have taken the financial world by storm. Being a growth asset rather than a yield asset, Bitcoin’s value has grown massively, recording returns upwards of 1,000% over the past 3 years, and upwards of 3,500% over the past 5 years. As at 31 January 2022, this equates to a 5-year compound annual growth rate of 105%, according to Glassnode Studios. This recent performance has created a new challenge for financial advisers, as although some digital assets have thus far provided excellent investment returns, they have not been accepted by traditional investors.

Some financial advisers, in response to client queries about digital assets, have expressed the sentiment that there is an emotional euphoria sweeping through the public around cryptocurrency, but that many of those who invest in cryptocurrency are doing so for the wrong reasons and do not truly understand what they are buying. For advisers, the consumer-driven hype around digital assets is very real, so it is important for them to be able to engage effectively with those clients who express ‘a fear of missing out’.

The extraordinary growth of the digital asset ecosystem has seen several thousand alternatives spawn in the past few years. According to digital asset exchange Kraken, four million Australians are likely to purchase digital assets in 2022. Further, research by online financial broker Savvy, indicated that 17.3% of Australians currently own some form of digital asset.

From an age demographic perspective, it is clear that digital assets are more popular with younger investors, with only 21% of all Australians willing to purchase digital assets, compared to 34% of Australian Millennials. The demand for digital assets has so far been largely consumer-driven rather than corporate-driven. Most Australians who purchase digital assets do so independently through online exchanges rather than through a financial adviser. The momentous growth of this asset class has understandably led advisers to tread carefully.

The difficulty of valuing assets like Bitcoin is another cause of hesitancy around digital assets. Satoshi Nakamoto, the pseudonymous ‘creator’ of Bitcoin, stated in an early forum post on Bitcointalk.org, “Sorry to be a wet blanket, but writing a description for this thing for general audiences is bloody hard. There’s nothing to relate it to.”

Bitcoin is so hard to describe, define or contextualise, it is little wonder that there is a lack of agreement as to what Bitcoin and other digital assets are. This makes achieving consensus on valuation near impossible. To make matters worse, internet memes like Dogecoin are bundled into the ‘digital asset’ basket right alongside Bitcoin, as well as outright scams like Bitconnect. Regardless of the ‘asset’, value is effectively narrative-driven, with quickly changing narratives playing an important role in price volatility. Fundamental financial techniques can be useful, but since Bitcoin is not just a financial instrument, but also a peer-to-peer software protocol, other valuation methods such as Metcalfe’s Law [a concept used in computer networks and telecommunications to represent the value of a network] may be used.

Financial advisers have also been hesitant to discuss digital assets with clients due to the lack of government regulation. Currently, Bitcoin is treated as property by the Australian Tax Office (ATO) and ASIC has released Consultation Paper 343 Crypto-assets as underlying assets for ETPs and other investment products, to determine the nature of Bitcoin., Australian digital asset exchanges are not regulated to the same extent as Australia’s primary securities exchange, the Australian Securities Exchange (ASX). Indeed, according to Savvy, 79% of Australians want to see digital assets more heavily regulated. Current US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Chair Gary Gensler is hinting that effectively all ‘digital assets’, with the exception of Bitcoin and a few yet-to-be-specifically-named others, are securities that should be subject to the SEC’s jurisdiction and oversight. In this context, it is understandable that advisers are wary of advising clients in this space.

A significant concern around digital assets is the exceptionally high volatility they have exhibited compared to traditional investments, an apprehension shared by both advisers and investors. While digital assets do experience higher levels of volatility, this sentiment implies that volatility cannot be managed. In actuality, various portfolio volatility management techniques exist and can be implemented.

These issues mean that many financial advisers are hesitant to approach the digital asset conversation with their clients. Despite this, client queries about digital assets are rapidly increasing. A Financial Standard survey conducted in September 2021, found that 77% of Australian advisers had received enquiries regarding Bitcoin and digital assets from their clients over the past 12 months. The survey also found that 82% of advisers did not feel equipped to respond to these enquiries. Further, some clients felt that their adviser’s lack of ability to recommend digital assets could lead to their financial detriment or may even be contrary to their best interests.

What is Cognitive Dissonance?

How should advisers who possess a healthy and reasonable level of scepticism about digital assets manage enquiries from clients who are highly enthusiastic? This type of discussion can elicit an emotional reaction which may be attributed to cognitive dissonance. Left unresolved, it has the potential to create risks for both the financial adviser and the client.

Put simply, cognitive dissonance is the discomfort one experiences when trying to reconcile two contradictory thoughts, beliefs or behaviours. A textbook example of cognitive dissonance can be illustrated by considering a person who continues to smoke cigarettes despite being aware that it dramatically increases their risk of lung cancer. An individual may rationalise this behaviour by believing that they need to smoke to deal with anxiety. Nonetheless to the external observer, a contradiction exists between the behaviour which is harming their health, and their belief that smoking will help them overcome a problem.

A financial adviser experiencing cognitive dissonance may find that it impairs their ability to give objective advice and prevent investors from making informed decisions. It is worth noting that cognitive dissonance is experienced as much by clients as it is by advisers. So, at the very least an adviser would benefit from learning how to identify and deal with their own and their clients’ cognitive dissonance.

Cognitive Dissonance Around Bitcoin

Financial advisers may experience cognitive dissonance in relation to digital assets, for instance Bitcoin, where they find that their beliefs about the asset, that is, their scepticism or prejudice—is contradicted by the behaviour of the asset—its prolonged success over more than a decade.

In addition, being a nascent asset class, digital assets are not included in asset class definitions, model portfolios or approved product lists (APL). Nor are they covered by professional indemnity insurers. However, like investment property, with clear and appropriate disclosures, advisers may be able to engage in a robust conversation with clients in which they discuss factual information about digital assets, if required. Clients may then be better informed if they choose to execute their own portfolio adjustments.

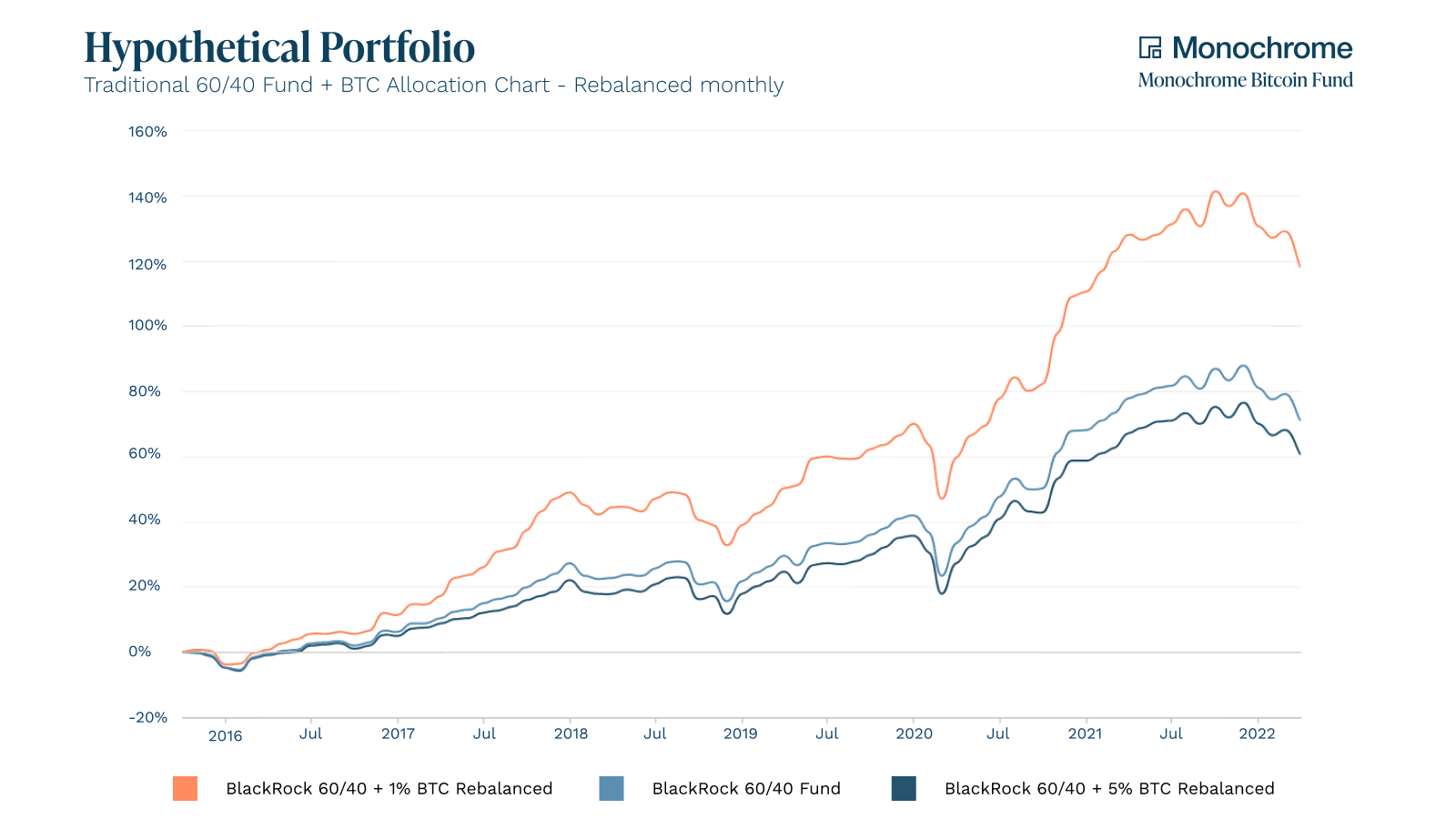

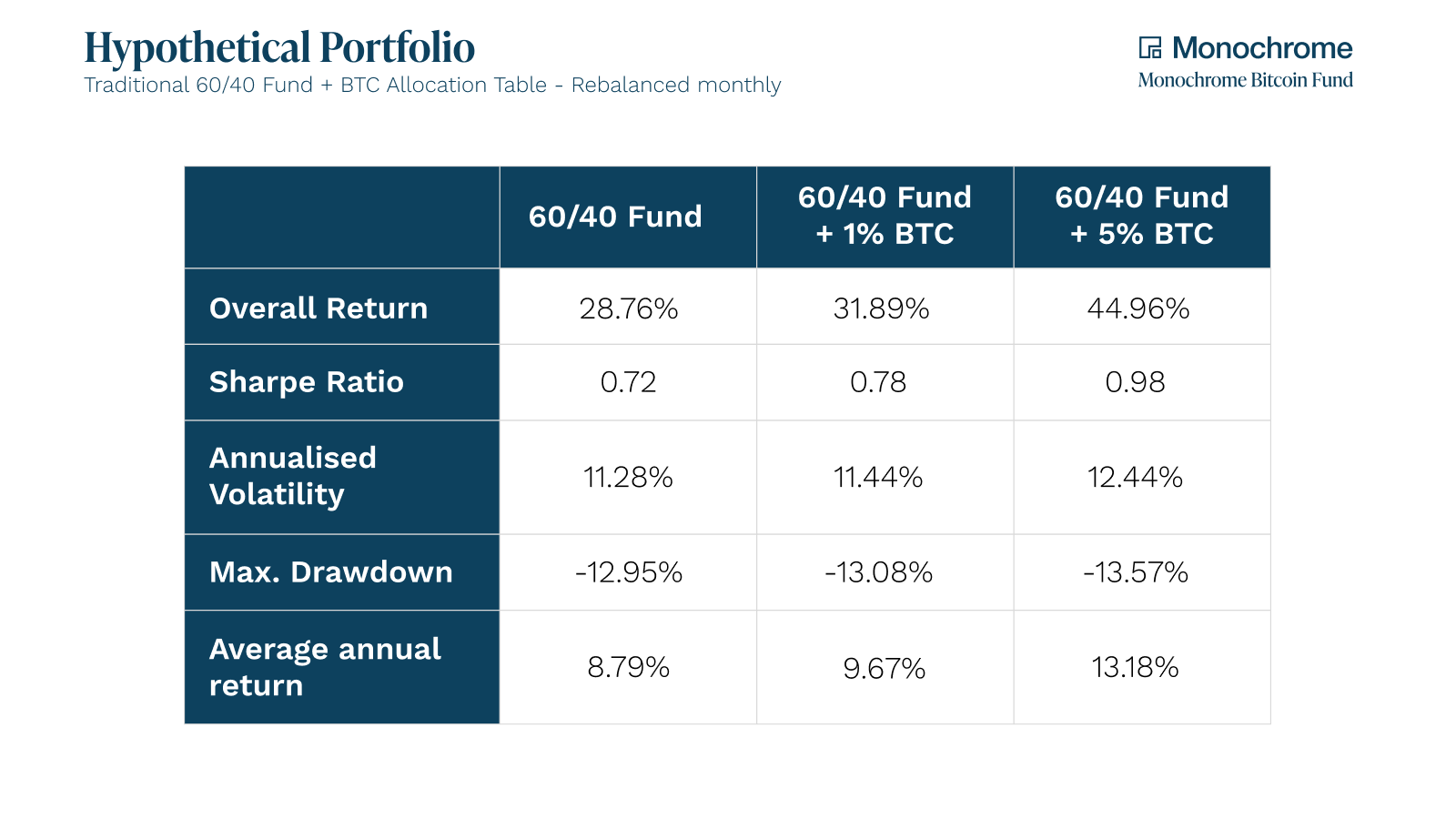

From an ethical and current regulatory perspective, if a financial adviser does not understand and has not investigated an asset, they cannot recommend the asset to a client. But at the same time, disregarding a whole asset class due to scepticism or a lack of knowledge may create a meaningful opportunity cost. Even a modest exposure to Bitcoin over the last 5 years would have created significantly better outcomes for investors. As shown in Figure 1, combining a managed fund such as the Blackrock 60/40 fund with a 1% or 5% Bitcoin exposure led to an increase in overall returns without drastically increasing volatility when rebalancing monthly.

Figure 1. Traditional 60/40 fund + BTC allocation

Table - Rolling 36 months, rebalanced monthly

If the client is knowledgeable about the product and wants to invest in it, then shouldn’t the financial adviser be sufficiently informed to engage in a meaningful conversation?

Effects of Cognitive Dissonance

The experience of cognitive dissonance around an asset class is a risk to manage for both the adviser and the client. Should an adviser discuss digital assets with clients in general, factual terms, or remain uninformed about digital assets and potentially leave clients to make their own, less well-considered decisions? Cognitive dissonance may prevent the adviser from investigating and deepening their knowledge of digital assets and consequently dismissing the asset class altogether. The good news is that there are many strategies to recognise and manage one’s cognitive biases.

Recognising Cognitive Dissonance

If a financial adviser finds that they have an emotional response to enquiries about digital assets, then they are likely experiencing cognitive dissonance and it is important to identify the cause. On reflection, the financial adviser may identify that they lack confidence in their knowledge of digital assets, in which case, there are potential options that they can take.

Firstly, financial advisers can learn about digital assets by completing online courses or research. Continuing professional development (CPD) courses are available and there is now an abundance of quality material to peruse. These resources can assist the adviser in understanding the asset class and facilitate better informed conversations.

Or financial advisers can simply limit the discussion about digital assets to an objective list of benefits and risks and thereby assist the client to make their own decisions. Again, caution must be taken to ensure that the discussion does not constitute financial product advice where there is no authorisation to provide this. For the present, these methods of enhancing their knowledge will allow financial advisers to participate in an intelligent conversation.

Conclusion

To meet their obligation to their clients now and in the future, financial advisers should make an effort to remain impartial and informed about different kinds of assets, including emerging assets. To this end, advisers would benefit from recognising any cognitive biases that may influence their decision making. As regulation of digital assets becomes more widespread, it is reasonable to assume that they will earn a place in APLs in the future. While the impacts of poor investment strategies are widely discussed, it can be equally important to consider the opportunity cost of investments consciously excluded from portfolios.

The content, presentations and discussion topics covered in this material are intended for licensed financial advisers and institutional clients only and are not intended for use by retail clients. No representation, warranty or undertaking is given or made in relation to the accuracy or completeness of the information presented. Except for any liability which cannot be excluded, Monochrome, its directors, officers, employees and agents disclaim all liability for any error or inaccuracy in this material or any loss or damage suffered by any person as a consequence of relying upon it. Monochrome advises that the views expressed in this material are not necessarily those of Monochrome or of any organisation Monochrome is associated with. Monochrome does not purport to provide legal or other expert advice in this material and if any such advice is required, you should obtain the services of a suitably qualified professional.

Related Articles

How to Value Bitcoin (2024 Update)

Valuing Bitcoin can be a challenge as, due to its abstract nature, there is “nothing to relate it to.” However, by shifting the lens through which we view Bitcoin, we can arrive at compelling theories through Metcalfe’s law, Stock-to-Flow, cost of production, market sizing and relating it to a technology start-up. Taken together, the following valuation models can be useful, though individually insufficient. Each model hosts criticisms, accommodating for improvements and adaptations.